“It’s her word against his,” says a middle-aged male juror in thick-rimmed glasses. “Someone of his experience wouldn’t do something so risky.” A woman to my right says the defendant is probably guilty, but maybe not beyond reasonable doubt. “But why would she lie?” asks another female juror.

Eleven strangers and I are discussing whether renowned children’s surgeon Simon Huxtable tried to rape Sally Hodges, the mother of a former patient. She says he tried to kiss her and then force himself on her. Huxtable says Hodges made up the allegation after he spurned her advances. Mobile phone records show he was at her home for 26 minutes but he told police he was there for only 10. His browsing history reveals he has an interest in rape porn.

I fiddle with a yellow label that says I’m juror number 11. Except I’m not really. The witnesses are actors, and we’ve been watching their testimonies on tablets at the Herbert Art Gallery and Museum in Coventry. The case is fictional, but shared pretence is engaging and our deliberations become heated.

The Justice Syndicate is part interactive play, part psychology experiment developed by audience-centric Newcastle theatre group FanSHEN and Kris De Meyer, a neuroscientist at King’s College London. It explores how we form and change opinions, our tendency to stick to initial instincts and how groups influence our views. De Meyer hopes that data gathered during the shows and their immersive nature will generate new insights into human decision-making.

It’s a subject we surely need to understand better. On Monday, protesters jostled and yelled at Tory MP Anna Soubry in Westminster, calling her a “fascist” and “scum” because of her pro-Remain stance. Across the Atlantic, divisions appeared to deepen still further as Donald Trump and leading Democrats traded insults over his demands for a wall on the Mexican border. The increasingly polarised and hostile nature of public discourse raises important questions. If humans have the capacity for reason, why do we make so many bad decisions? How come people cling to extreme or irrational views in the face of facts? And can psychological insights lead to better, more rational decisions?

The starting point for many who grapple with these questions, including those behind The Justice Syndicate, is the work in the 1950s of American social psychologist Leon Festinger. Based on a basic human desire to be consistent, Festinger said we compare ourselves to others to evaluate our own opinions and abilities, and that those in groups with diverging opinions will either seek to move towards consensus, ostracise individuals with opposing views or form entrenched factions.

He also outlined how, when humans hold contradictory ideas, or their actions conflict with their beliefs, they suffer a form of mental discomfort called cognitive dissonance. His PhD student Elliot Aronson fleshed this concept out, showing how this is especially likely to lead to poor decision-making when it concerns something that is important to our self-image. “If I see myself as someone who is smart, competent and kind, and you give me some information that I have done something foolish, immoral or hurtful, I have a choice,” says US social psychologist Carol Tavris, co-author with Aronson of Mistakes Were Made (But Not By Me). “I can revise my view of myself, or I can dismiss the evidence. Most people take the least painful path and dismiss the evidence.”

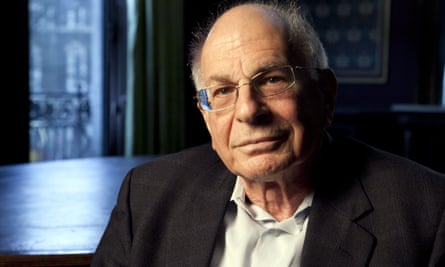

These pressures can lead to confirmation bias – the tendency to pay attention only to information that confirms our existing beliefs. It is perhaps the best known of human biases. During the 1970s, Nobel prizewinning psychologist Daniel Kahneman outlined a series of other mental shortcuts that can lead us astray. The “availability heuristic”, for example, may mistakenly convince us that car travel is safer than flying. A £100 pair of jeans might seem like a bargain if reduced from £200, even if they cost £2 to make, thanks to the “anchoring effect”. And the “representativeness heuristic” can mislead gamblers into thinking they are due a win following a string of statistically unrelated losses. Kahneman went on to outline how the brain uses rapid, intuitive processes to make some decisions and slow, more conscious and deliberative processes for others.

Some argue our cognitive biases only look strange if we see human reasoning individualistically. French cognitive psychologists Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber argue in their 2017 book The Enigma of Reason that as highly social animals, we are deeply concerned with appearing to be wise, competent and trustworthy to others. Our reasoning capabilities therefore evolved not to reach the most logical solutions to problems but to help us argue our case and justify our positions. “We are constantly justifying ourselves and seeking to persuade others that we are the kind of person they want to cooperate with,” says Mercier, of the Jean Nicod Institute in Paris. “From this perspective, it makes no sense to hold on to arguments that contradict your point of view, but it does make sense to have a confirmation bias.”

In a 2015 study, Mercier asked participants to tackle a series of reasoning tasks, and provide justifications for their choices. When later asked to evaluate their own statements disguised as those of others, more than half disagreed with themselves.

Political polarisation has been a hot topic since 2016, the year Britain voted to leave the EU and Donald Trump moved into the White House. De Meyer, however, has been tracking the phenomenon since George W Bush’s narrow victory in the 2000 presidential election, through the rise of the Tea Party movement, anti-Barack Obama sentiment and the rumbling acrimony over climate change.

Aware of the insights psychology had to offer, he and film-maker Sheila Marshall produced the 2016 documentary Right Between Your Ears, which featured American Christian radio host Harold Camping and his followers, who believed that God would gather up his chosen few and then destroy the Earth with huge earthquakes on 21 October, 2011. It captures the intensity of the cognitive dissonance suffered by believers, who had left their jobs and sold their homes, on realising the end had not in fact been nigh.

There have been some 20 Justice Syndicate shows since early 2017. The software on which it runs also gathers research data, tracking how consistent participants are when asked three times during the piece which way they are leaning, and how long they view pieces of evidence for. An initial analysis of recent shows found that almost half of participants failed to change their initial leanings at all, despite the introduction of new evidence.

“Individuals take very different views on what bits of information are important,” says Joe McAlister, the computational artist who developed the software. “It’s taught me that people have a lot of different and unusual biases, which is fascinating but also quite terrifying.” The allegations of sexual assault made against Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein and US judge Brett Kavanaugh both affected Justice Syndicate debates and verdicts. McAlister says younger participants have focused more strongly on issues of consent.

Recent failures to repeat experiments that support important concepts in psychology have led to a loss of confidence in the discipline. Some blamed the use of highly artificial decision-making tasks for this “reproducibility crisis”. De Meyer believes interactive theatre can produce more realistic results. “It allows us to recreate something with a certain level of realism, and opens up doors to do psychological research in a new way that we couldn’t do 20 years ago.”

Others seem to agree. In December, De Meyer and FanSHEN produced a new piece, commissioned by the Cabinet Office, to probe people’s reactions to a national power grid failure. Work on a scenario about someone dying due to medical negligence will begin next month. De Meyer wants to use the format to study why people are more likely to blame those of different ethnic groups to themselves for errors.

He also hopes his work can help explain rising political polarisation. Research by US thinktank the Pew Research Centre shows a growing gulf in the views of Republicans and Democrats on key topics such as race, the environment and the role of government. Another study shows Americans increasingly dislike or even loathe those who support the party they themselves oppose.

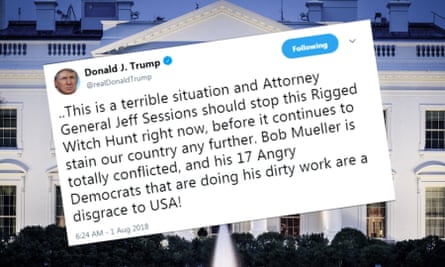

Many blame social media for fanning the flames of division. “The way people use social media and select their own online news sources keeps them in their own little confirmation bias bubbles,” says Tavris. “Tweets go viral when they really resonate with a group or really anger a group,” says De Meyer. “Social media seems to be amplifying existing divisions and probably making them worse.”

Psychology offers insights, both to individuals who want to make better decisions by learning about their own reasoning powers, and those seeking the secrets of persuading others. In a 2014 study, Mercier and colleagues found only 22% of participants could solve a reasoning task on their own, but when small groups discussed their thinking, this rose to 63%. “If people are reasoning on their own or only with people they agree with, nine times out of 10 they will stick to biased positions and you are going to get polarisation,” he says. “But if you take a group of people with some kind of common incentive but who disagree about something, then reason can help them get a better answer.”

Back in our mock jury room, and an initial show of hands reveals that, after hearing the evidence, we see Simon Huxtable as guilty by a slim majority or 7-5. “She was drunk and upset,” argues juror number four, a young male. “But what would she have to do for people to believe her?” asks a female jury member, who adds a not guilty verdict would send out the wrong message to other victims. “His sexual fantasies, however extreme, are irrelevant,” says a male juror. “We need to focus on the facts of the case.”

Another vote shows that 10 minutes of discussion has shifted opinion to 7-5 for not guilty.

At this point, I notice a matriarchal juror across the table is speaking both frequently and sensibly and that many participants are looking in her direction when they speak. She is arguing with increasing conviction that the evidence against Simon Huxtable is merely circumstantial. A short while later, we vote again, reaching a not guilty verdict by 10-2. During a debriefing session, Dan Barnard of FanSHEN describes some or the psychological concepts underpinning the show and encourages us to consider how they affected our decisions.

The show’s creators believe greater understanding of the mental triggers that affect our own decisions and those of others could help us all become a little more open-minded, tolerant and rational. “The most powerful form of learning is experiential,” says De Meyer. “My hope is that by making people aware of how they are thinking and behaving, it helps them to deal with real situations in which emotions and instincts might otherwise take over.”

The Justice Syndicate is running on 9 February at the National Justice Museum, Nottingham; 11-23 February at the Battersea Arts Centre, London; and 14 April at the Pleasance theatre, Edinburgh as part of the Edinburgh international science festival

Test your powers of reasoning

1. A bat and a ball cost £1.10 in total. The bat costs £1 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?

2. It takes five machines five minutes to make five widgets. How long does it take 100 machines to make 100 widgets?

3. A patch of lily pads on a lake doubles in size daily. It takes 48 days for it to completely cover the lake. How long would it take for the patch to cover half of the lake?

Check your answers below. If you struggled, don’t worry, you’re in good company. Just one in six of more than 3,000 Americans, mostly of college students, got all three right. A third failed to get any correct. US psychologist Shane Frederick developed the cognitive reflection test in 2005 to measure the degree to which people either go with their gut instinct or take their time to reflect on simple but misleading puzzles.

Answers: 1. 5p. 2. Five minutes. 3. 47 days.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion